People have always felt a mysterious attraction to the Greater Kruger National Park area. Long before it had been named this, the area attracted ancient tribes that made it their homeland, leaving for us intricate relics and artwork to find and observe in our modern age. The Stone Age Bushman of the Kruger National Park area who occupied this wilderness between 500,000 and 100,000 years ago, survived of the land with wonderfully fashioned implements that they used in their everyday lives in the savanna. These early savanna pioneers hunted and gathered for survival, leaving their stories engraved or painted on rocks throughout the Park. For thousands of years these people lived in harmony with the land and all her creatures. There are many Cultural Sites situated throughout the Park that showcase this rich and diverse history. We like to share these accessible sites with our guests on our overnight safaris.

Stone Age

Archaeologists have discovered that early humans roamed through the Lowveld as far back as one and a half million years ago. These ancient humans left clues for us about their prehistoric lives, such as stone tools, their skeletons and the bones of the animals they ate. From this evidence, anthropologists can get some idea of how they lived and what they looked like.

Kruger National Park tribal history starts with hunter-gatherers, like the San people, who roamed the present-day national park region. A lot of their rock art can be found at historical sites within the Kruger National Park. The Nguni herders, who lived in most of south-east Africa, also roamed the Park with their cattle.

For centuries the San lived without competition for resources, but as early as 500 AD, more technologically advanced people, the Bantu-speaking Nguni farmers, immigrated into the Lowveld and settled along the banks of the Limpopo, Luvuvhu, Shingwedzi, Letaba and later the Sabie and Crocodile Rivers. They brought crops and herds of domestic animals and the secret of their metalwork. This was the beginning of the Iron Age in Southern Africa. Archaeologists have discovered that for hundreds of years this new civilisation lived alongside the San, sharing the abundance as provided by the bush. As more people moved into the area, the San were gradually pushed out, although scattered groups still inhabited the area as late as the 19th Century.

Iron Age

The Iron Age in the Kruger National Park region is generally dated from around 500 AD to the arrival of European colonizers in the 19th century. During this period, the region saw the emergence of more complex societies, including the Mapungubwe Kingdom and the Great Zimbabwe Kingdom.

On the road between Phalaborwa Gate and Letaba Rest Camp, there’s a late Iron Age site called Masorini on top of a hill. The Sotho speaking Ba-Phalaborwa tribe lived there during the 1800s. They developed an advanced mining industry. They smelted iron ore and traded their products like spears, arrowheads and simple farming tools.

Dome shaped clay furnaces found on the site were used to smelt the iron ore. Skin bags attached to the end of clay piping were used as bellows. These clay pipes led into the dome furnaces through 2-3 openings. The ore would flow into the middle of the furnace due to the inward sloping floors and once cooled would be removed and stored. When there was enough smelted ore for production it would be reheated, beaten (to remove impurities) and moulded into the desired products such as spears, arrowheads and simple agricultural implements.

For over a thousand years, trading was an integral part of life on the sub-continent with trade taking place inland between different groups and along the coast with Arab and Chinese merchants. Due to this, various trade routes were established, with an important one bypassing Phalaborwa where metal was worked and traded for glass beads, ivory, animal products and food. Trade between the BaPhalaborwa at Masorini and the Venda in the North and the Portuguese on the east coast, increased smelting and ensured a greater independence for them.

The remains of the huts that they lived in, and their furnace have been reconstructed by the local Ba-Phalaborwa people who now live on the borders of Kruger National Park. There’s a museum and picnic spot at this historical tribal site.

In about 1550, groups of people from a large cultural civilisation who lived in what is currently Zimbabwe, moved south and crossed the Limpopo River. They settled in an area called Pafuri Triangle. The area is also called Makuleke. It’s a piece of land bounded by the Limpopo and Luvuvhu Rivers at the northern most tip of Kruger National Park.

One of the settlements they made was called Thulamela. It was a walled city on the southern bank of the Luvuvhu River. Lots of golden jewellery, Chinese porcelain and Arab glass beads have been found in the ruins.

Modern Era

International trade in South Africa began about 1000 years before gold was discoverd on the Witwatersrand. Copper from Phalaborwa and Balule, salt from Eiland, and crops like sorghum and beans, had long been traded locally. But the lowveld and the interior had far more exotic goods that attracted the attention of Arab traders in search of riches and new products. Africa had 'white gold' in the form of elephant ivory and It had 'yellow gold', the precious metal that kings and sultans desired.

It wasn't until 1725, that the first Europeans encountered the hostile Lowveld. Francois de Cuiper, a Dutchman, crossed the Lebombo Mountains. No sooner had he entered the present-day Kruger National Park, that he was attacked at Gomondwane and beat a hasty retreat to the coast. For another century the area remained a mystery to adventurous Europeans, who had already circumnavigated the World but had not yet conquered or colonised Africa, its wildlife or its people. In time the Lowveld became known as the 'White Man's Grave'.

The first European to return, was Joao Albasini, a Portuguese trader who ventured from Delagoa Bay in 1830, and began establishing trade links inland. Albasini's larger than life personality, his willingness to learn the local language, and with the help of the warrior chiefs Manungu and Jozikhulu, enabled him to survive. People living along the Sabie River felt they were under his protection and in turn protected him.

By the end of the century, hunting mania had wiped out the Lowveld's huge herds of game. In 1898, President Paul Kruger proclaimed the area between the Crocodile and Sabie Rivers as the Sabie Game Reserve. This was fortunate timing, as for the next 4 years, politicians, hunters, and fortune-seekers were too busy fighting the Anglo-Boer War to care about wildlife conservation.

After the war, the British victors reproclaimed the Reserve. They set about clearing the way for the protected area. This involved the forced removal of local inhabitants and in 1903, between 2000 - 3000 people were moved out of the Sabie Reserve. Similar removals were conducted throughout Kruger's history. In 1969, after many years, the Makuleke people were moved out of the Pafuri area. Land claims today continue the dispute between the need to conserve a natural heritage, and the people's need for both land and work.

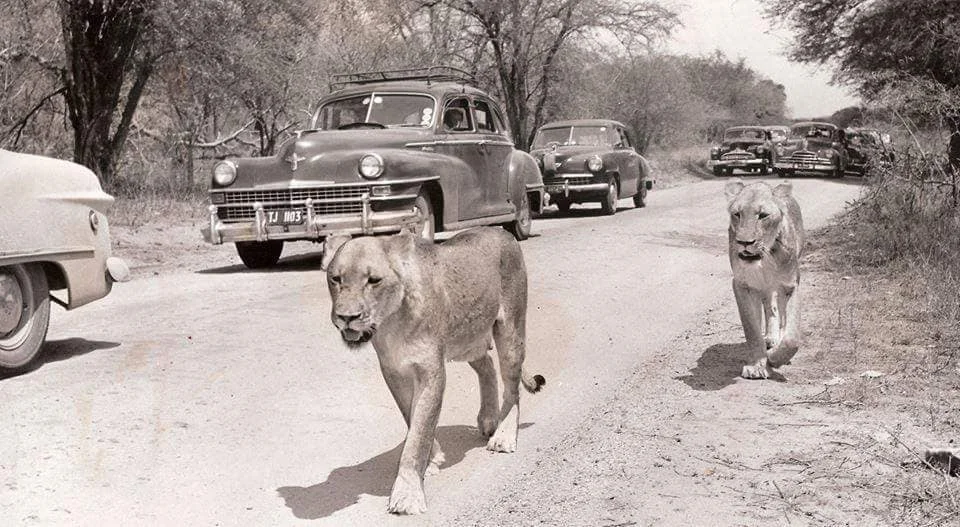

In 1927 three cars entered the Park. Two years later there were 850 cars visiting. Over the next 50 years some 150 000 people visited the Kruger National Park annually. Today there are over 1 000 000 wildlife enthusiasts who visit the Park every year, enjoying the fruits of a long, fascinating and hard-won battle to create one of the finest Game Park in the World.